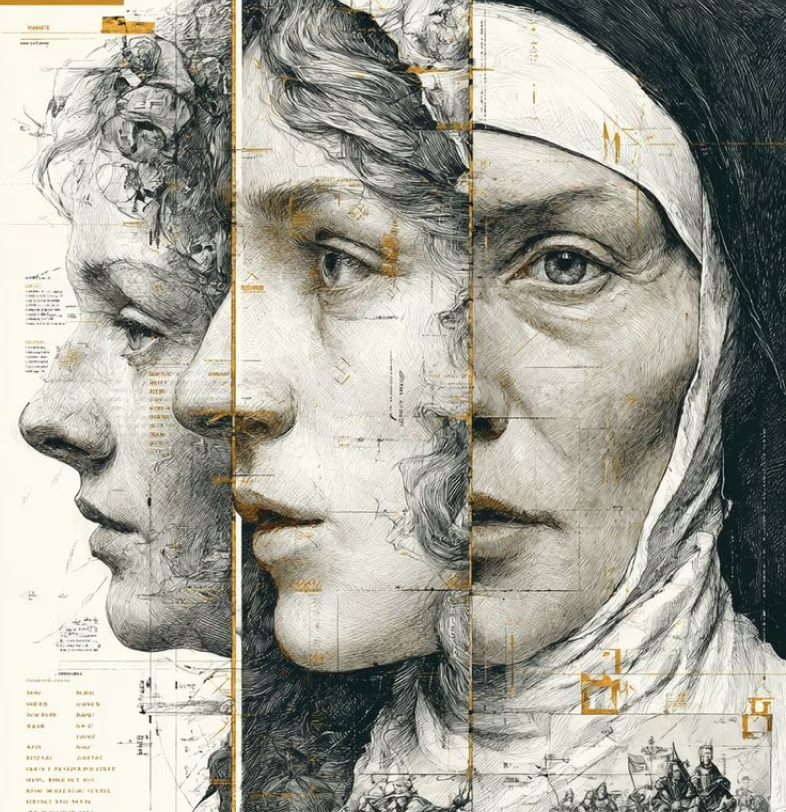

Many women have suffered from the Matilda Effect: their discoveries were minimized, credited to others, or forgotten.

Here are seven exemplary stories, placed on a timeline, showing how science has sometimes erased its own pioneers.

Astronomy and Mathematics Teacher and commentator of mathematical works. Erasure: her violent death and male-dominated legacy overshadowed her contributions and place in the history of ancient science.

Learn moreTranslation and Commentary of Newton’s Principia Spread of Newtonian ideas in France. Erasure: her role as translator-theorist was long reduced to a “translator” rather than a full-fledged scientist.

Learn morePaleontology Discoveries of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs on the cliffs of Lyme Regis. Erasure: her findings were often published or credited to male scientists who claimed her data.

Learn moreEarly Computing Notes proposing an algorithm for Charles Babbage’s analytical engine (considered the first “program”). Erasure: her original role was underestimated for decades, often portrayed as a mere assistant.

Learn moreAstrophysics Thesis showing that stars are mostly composed of hydrogen (revolutionizing stellar composition). Erasure: her conclusions were initially questioned and partially credited to male colleagues before being recognized.

Learn moreNuclear Physics Theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (with Otto Frisch) after Otto Hahn’s experiments. Erasure: the discovery of fission was honored with the Nobel Prize awarded to Hahn, without full recognition of Meitner’s role.

Learn moreBiophysics “Photo 51” (X-ray diffraction) crucial to solving DNA’s structure. Erasure: Watson and Crick used her image and data without proper credit at the time; Franklin’s recognition came largely posthumously.

Learn more

Thousands of women scientists have likely been victims of the Matilda Effect throughout history. This term describes how discoveries made by women were often credited to male colleagues or ignored by the scientific community.

Although exact numbers are difficult to establish, historians agree that this phenomenon affected many female researchers in the 19th and 20th centuries and still persists today in subtler forms in recognition, publications, and scientific awards.